Photography Journal

Meeting my dad 12 years after his passing

For the past two years, I’ve been working on a film about my father, artist Vyacheslav Shraga. My parents divorced when I was five, and I barely knew him. Twelve years after his passing, I set out to understand him through the people who truly knew him — and through the complicated story of his life.

The process was an emotional roller coaster. I felt anger, admiration, grief, and awe — often all at once. He was a brilliant artist who inspired many, but also hurt those closest to him, including me.

The idea for this film followed me for years. It only took off after I met Tobias Hauri, a Zurich-based art collector who owns over 300 of dad’s works. He invited me to create this documentary as part of his research project.

Now the film is finished. What once felt impossible is done — and it feels good.

These days, I’m more and more drawn to capturing family stories. I do this a lot for humanitarian organizations and private clients through photography, interviews, and custom documentaries. There is always a certain urgency to it: “We should do this before it’s too late.”

If you know someone who feels the same, please send them my way.

And now, the movie:

Freedom is…

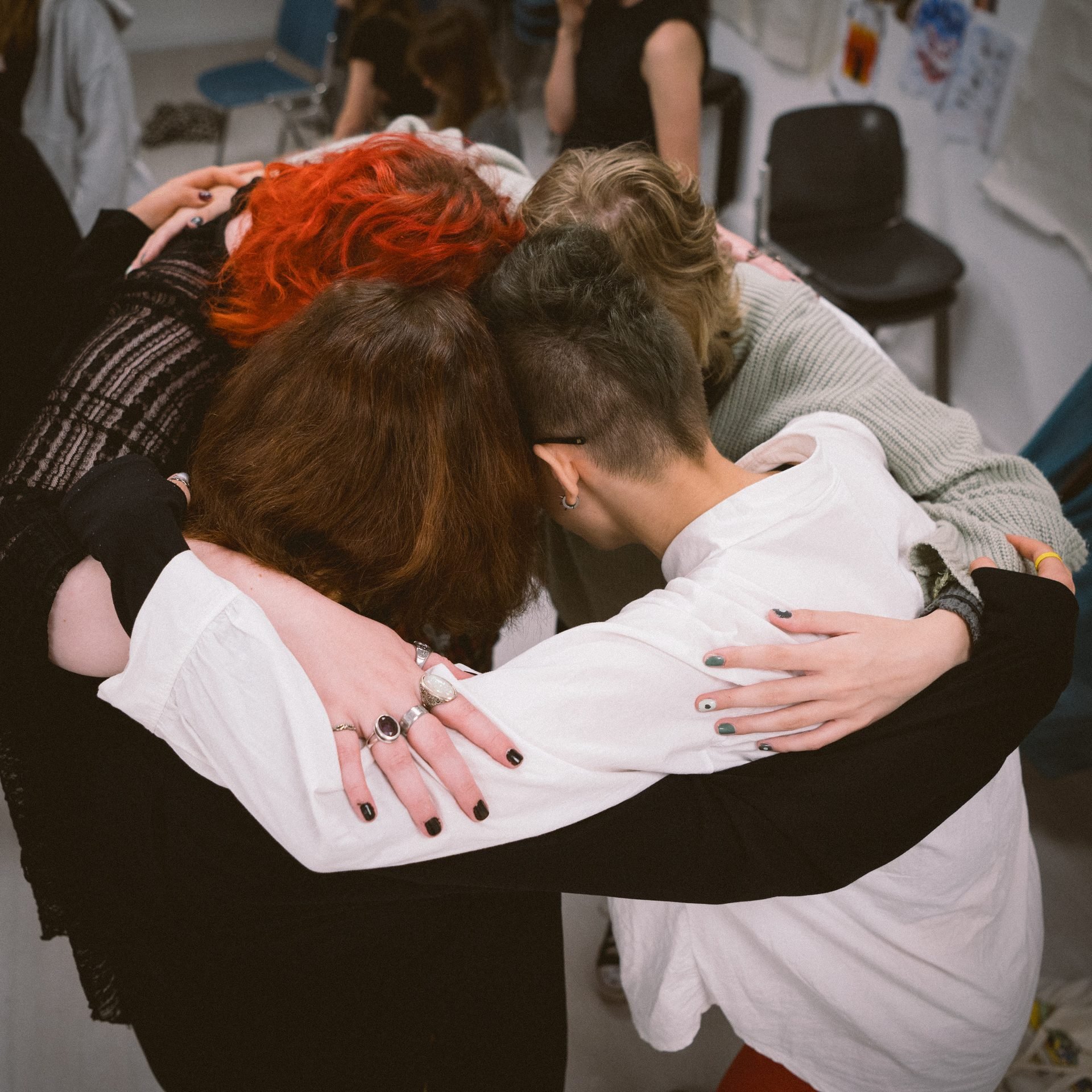

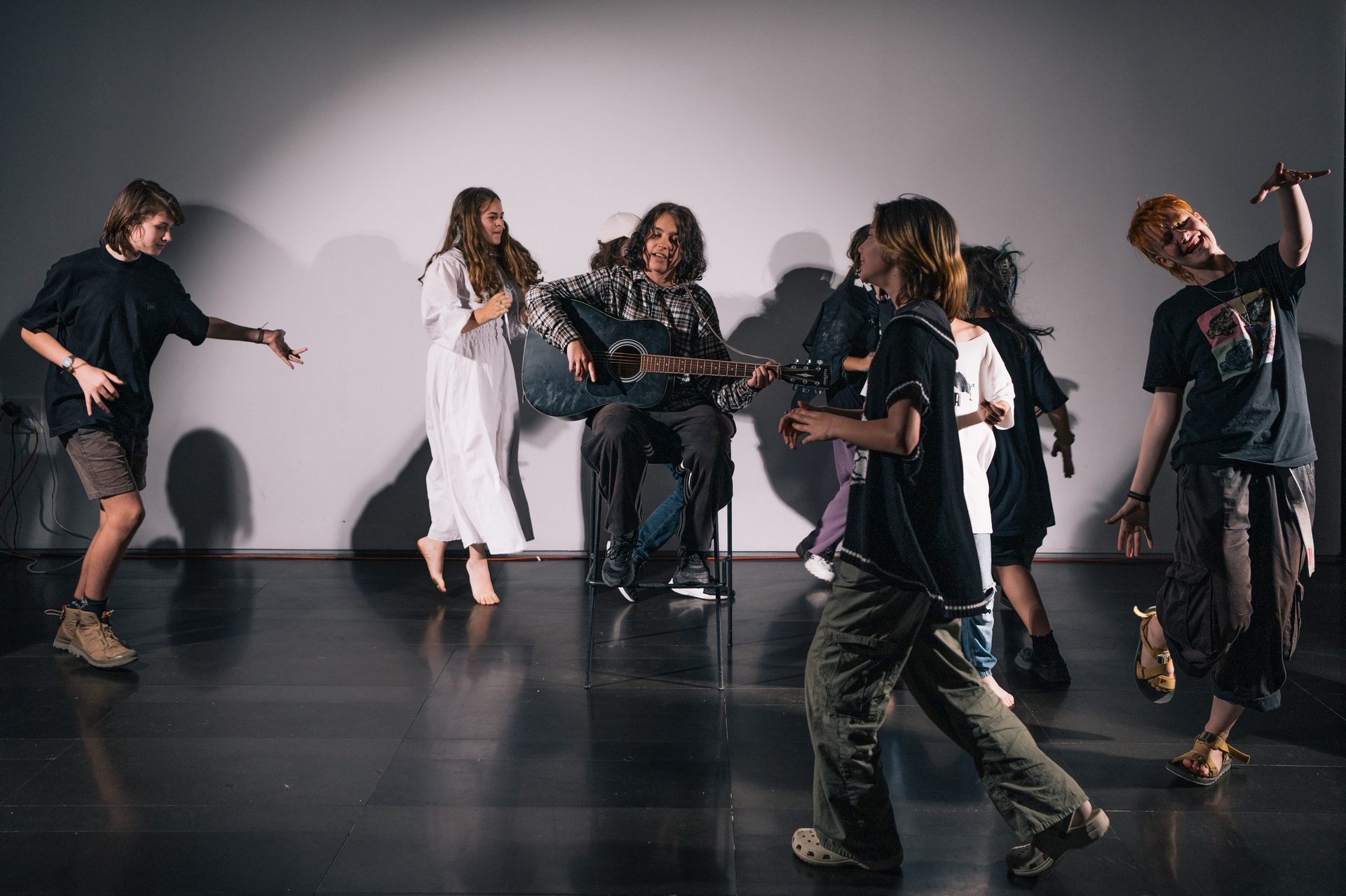

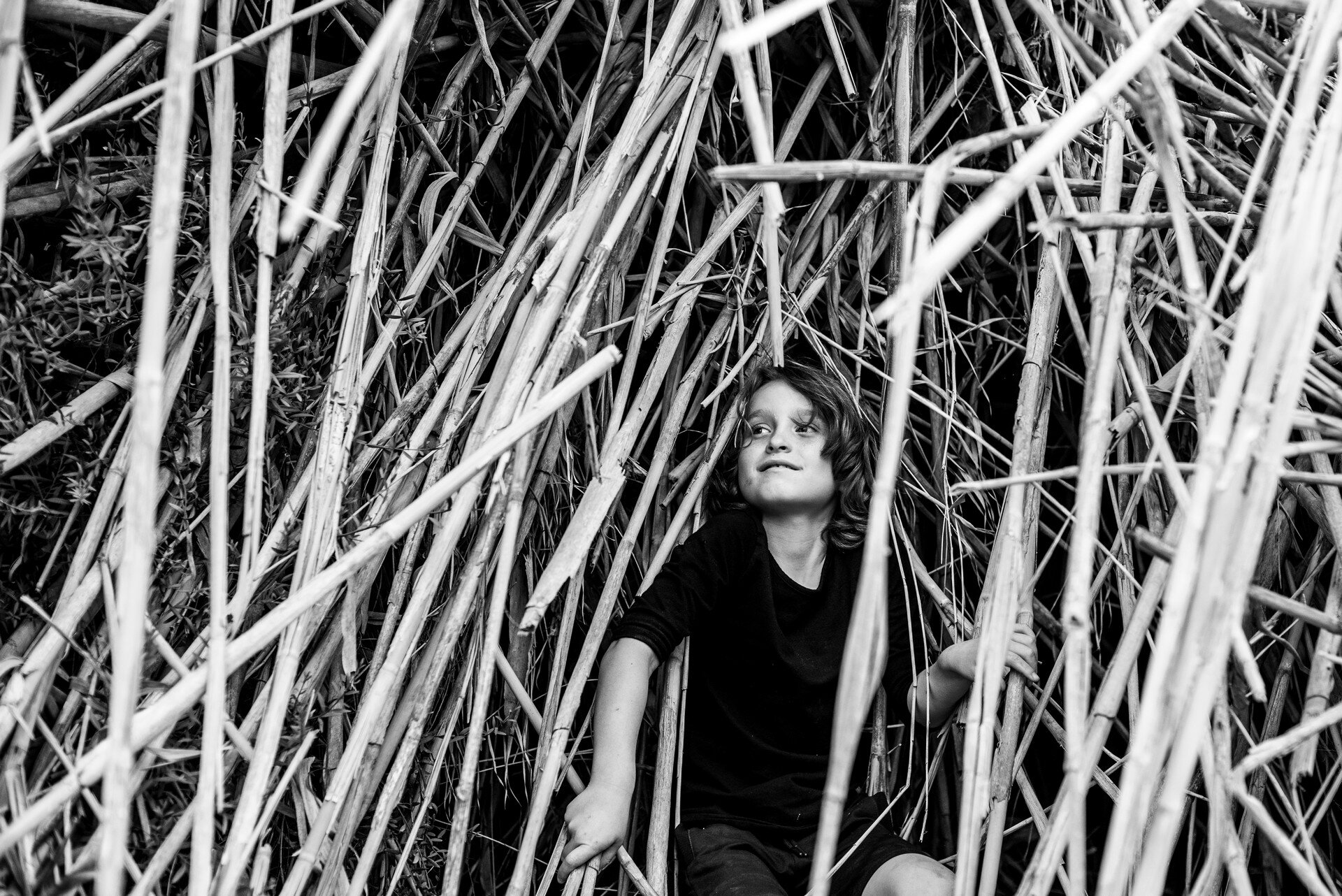

The Walks project helps young new immigrants from Russia and Ukraine find their place in Israel. One of the initiatives of the project is called “art laboratory”. It is a creative camp held once every several months. During the camp dozens of kids gather for 4-5 days to explore one specific existential topic. Each art laboratory ends with a performance for the public.

In April 2024 the art laboratory offered teenagers to research the meaning of “freedom” at the Museum of Jewish people ANU in Tel Aviv. This was the third camp by The Walks that I’ve been documenting.

Besides making still photographs, during all 4 days of the camp I was capturing some footage which afterwards I edited into a short clip:

Unbroken in Ukraine

“We won’t allow the war to steal our youth years.”

Pictures from Ukraine in 2024

Ukraine never fails to surprise me. From the trip of January 2024, I brought back the memories of the sparkling eyes of young adults from Kharkiv, Sumy, Poltava, and Odesa. They explained to me that in 2023, a year into the war, something clicked in them that made them switch from being depressed, lost and frightened to being fiercely active. “We realized that the war isn’t going to end any soon. We’ve got only one life to live, and it’s happening now. We can’t let the war steal our youth.”

I was amazed by the atmosphere in Ukrainian cities being vibrant, lifeful, and unbroken.

See the pictures:

Voices of refugees

Two weeks into the war I found myself documenting the refugee crisis on the borders of Ukraine — in Hungary, Moldova, and Romania. There I was documenting disaster response, taking pictures and filming interviews with the refugees

I was shattered when the war began. I still am. I was silenced. It was as if all the worst nightmares suddenly came to life. Dwarfed by the events, I was watching an unstoppable wave of a disaster rolling upon me. Never before I’d felt so useless and cornered.

My mom is from St. Petersburg, Russia, and my dad was from Mariupol, Ukraine. And now my motherland is in a deadly fight with my fatherland.

I knew I needed to do something in order to stay sane. The best I could do was give a voice to those who suffer most. That’s my job, after all. In 2023 I’m celebrating my 10 years in humanitarian photography.

I collected refugee evidence stories in Ukraine in 2015, ISIS refugees stories in Jordan, and I never stop gathering WWII memories, so just two weeks into the war I found myself documenting the refugee crisis on the borders of Ukraine, in Hungary, Moldova, and Romania. There I was documenting disaster response, taking pictures and filming interviews on the assignment of the JDC.

I came back home broken and inspired at the same time. Broken by all the sufferings of Ukrainian people whose stories aren’t much different from those of the 2nd World War survivors. Inspired I was by the amount and quality of kind, strong, selfless volunteers who jumped into their cars or took the nearest flight to the Ukrainian borders to offer their help.

One day in Siret, a huge disaster relief hub next to the Romanian-Ukrainian border, an influx of refugees paused for a few hours. I had a chance to take a breath and look around. I had to admit that it felt great to be there, surrounded by hundreds of people from all corners of the world, who were there to fight the evil with kindness.

I gathered dozens of refugee testimonies whose lives were saved thanks to the JDC’s efforts. Here I’d like to share with you a tiny bit of the first-hand pieces of evidence.

Siret, Romania, right next to the Ukrainian border. The buses are allowed to make a short stop there but must leave after 5 min to avoid clogging the border crossing. JDC volunteers use this time interval to quickly provide refugees with food, hygienic products, medicines. I used this time to quickly film interviews. This one - with a family who miraculously escaped from Mariupol.

Palanca, Moldova-Ukraine border crossing. A farmer dropped off her child in Poland and returns home to take care of her farm near Mykolaiv.

Chisinau, Moldova. JDC-operated improvised transportation hub for Ukrainian refugees. The story of a family who fled Kharkiv

Chisinau, Moldova. JDC-operated refugee shelter in the Jewish community center. A family of refugees from Chernihiv.

Hungary, Záhony. Ukraine border crossing. A boy reflects on his journey from Ukraine.

I can see the whole world

Nearly blind and homebound, Victor lives alone in a small apartment and requires constant care. He has a developmental disability that makes him see the world like a young child and stay vulnerable and innocent.

Victor has a developmental disability that makes him seem like a young child, innocent and vulnerable. Unfortunately, he also has the health problems of a much older man. Nearly blind and homebound, Victor lives alone in a small apartment and requires constant care.

Desperate, yet Cheerful

Victor spends his days pursuing two passions. He loves to draw detailed, realistic depictions of cars, trains, and airplanes. Victor’s poor vision requires him to press his face close to the paper he is working on. His artwork takes much time and focus to complete.

Victor’s other interest is music. He has an old accordion that he plays, singing along in his deep baritone. An elderly family friend calls him occasionally to provide him with new music, dictating notes and lyrics that Victor slowly writes down and then learns on his own. All of the music Victor plays is from memory, as the written music is hard for his failing eyes to make out.

Friendly and social, Victor enjoys being with people. The monthly support of IFCJ has been essential to Victor’s survival, allowing him to remain in his home thanks to the assistance it provides. Volunteers of The Fellowship sometimes find him near his window, looking through binoculars into an empty square outside. While the homecare workers see dull, snow-covered Soviet-era architecture, Victor envisions a magic garden and much more.

“I can see the whole world through my binoculars,” Victor says.

Pictures and interview created on assignment of The Fellowship of Christians and Jews

Zabereg photo project: Accomplishment

A long-term project about disappearing villages along Pinega river in Russia resulted in a photo book and an exhibition

It took me 11 years to accomplish my personal documentary project about Northern Russian villages. My goal was to go beyond documenting the region at a certain moment in history: I wanted to show how the situation evolves with time. I returned to the same villages over and over again, year after year. At some point, I felt how from a total stranger there I turn into someone whose next visit is expected. The region has changed a lot since 2008 when I began shooting there. Many villages got empty, the remaining infrastructure fell apart, schools, daycare centers, shops, and clubs shut down, public transportation became unavailable. At the same time, I met young new settlers who came from the large cities willing to fulfill their lives far away from civilization with a hard farmer’s labor, and maybe to set a new trend opposing global urbanization.

There was a handful of main characters in this project: a group of elderly women all living in one village. By the time I went on my last trip in 2019, only two of them remained - Maria and Rimma. I stayed at Rimma’s and visited Maria who already couldn’t live on her own and moved to her daughter’s. Right after I came back from that trip, I was told that Rimma has left the village. Shortly afterward terrible news followed: Maria passed away. That was a sign to me that my project is over. It couldn’t go on without these two women.

I sat down to put together a book and an exhibition. With help of my incredible friends I was able to craft a stunning book and on the day of my 40th birthday I opened the exhibition at the Museum of Natural History, Jerusalem.

Here are the names of those who made it possible:

Ola Netta Levitsky - book design, illustrations

Eugenia Shraga - book editing, illustrations

Sasha Iudashkin - book cover

Eugenia Kirshtein - exhibition design

I dedicated a separate page to this project on my website, for more information click here: ZABEREG project

Childhood fears

A glimpse into wartime childhood memories

Rita tells: “When I was 2, I took a bite out of pear and saw a worm. I was frightened to death! When I was 4, my mother took me to a theatre, and all those flashing lights scared me so much that I ran away.

When I was 5, the war began. There was death, hunger and sufferings all around. I nearly died of malaria. Our barrack caught on fire. I often collapsed because of hunger. But I was never frightened during the war, not for a moment.”

When honouring is painful

"Better late than never" conception doesn't work when it comes to the acknowledgment of injustice. No monuments, books or movies can heal the pain after a person is gone. Eleonora's father, Sasha Pechersky, was a true hero, a leader of an uprising at Sobibor Nazi camp who saved dozens of Jewish lives. He should have been praised on all corners. Instead, he was ignored and humiliated. 30 years after his death the country is trying to fix this.

Eleonora is the only daughter of late “Holocaust hero, Sobibor Resistance Leader, and Hostage of History” as labels him a subtitle of a book called “Sasha Pechersky” by Selma Leydesdorff. “For the last 15 years I’m drawing a lot of attention from mass media, directors, writers, authorities. But nobody is interested in me – everyone wants to talk only about my father”. Eleonora is disturbed by all the buzz surrounding her father’s memory for one simple reason: it’s too late. While he was alive, he never got any attention. Just the opposite: he was ignored and humiliated in various ways by the Soviet regime. In 1948 he was fired because of his Jewish nationality and for the 5 next years all his attempts to find a job failed. Authorities didn’t want to listen to his story and recognize that he was actually a hero, a leader of a unique operation that helped 53 Jews escape from death at Sobibor Nazi concentration camp. Holocaust remained a suppressed topic during most of the Soviet era. An essay about Sobibor uprising written by famous Soviet writer Kataev was banned from publishing.

During the war, Sasha Pechersky’s family had no doubt that he was killed. Later he admitted that there were moments when he would prefer to be killed instead of going through all the humiliation. After he organized an uprising at Sobibor death camp and escaped with his mates from Nazis, he was detained by Soviet authorities who considered anyone ever captured by Nazis as traitors. Instead of praising Alexander’s heroism and courage, the authorities treated him as a criminal and sent him to a penal military unit for certain death - disciplinary battalions had no mercy to their soldiers. Statistically, no more than 1 out of 10 survived in such units. To his “luck”, Alexander was heavily wounded in a battle and sent to a hospital. That’s how he escaped.

When in 2018 a monument of Sasha Pechersky was inaugurated in Rostov, Eleonora who never goes out because of her Parkinson's disease, put together all her strength and attended the ceremony. A city mayor approached her and asked: “So, I guess you are happy now?” “How can I be happy when all of it is taking place 30 years after my father passed away?” she replied despairingly.

Eleonora’s childhood was full of war-time drama. Being a little girl she underestimated the danger and the cruelty of the moment. The summer of 1941 when the war began she spent like any other summer - in a small village not far from Stalingrad, with her grandmother. One day the village was occupied and set on fire by Nazis. Everything was burnt down. “The village was already in flames when I first saw Nazi aircrafts dropping bombs. I ran to my grandmother shouting “Nanny, they are dropping air balloons, let’s go catch them!”” 7-years-old Eleonora and her old grandmother had to leave their place and look for shelter. Eleonora went barefooted with nothing but a summer dress on her. All her clothes were destroyed in the fire. “I remember how we walked across a field when a Nazi aircraft approached. It was flying low and slow, it was there to kill. My grandmother pushed me to the ground and covered me with her body. She was heavy. I began crying and asking her to get off me, but she only whispered - “Hush, hush, keep silent, don’t let them discover us.”” Only by happy chance, Eleonora escaped death multiple times during the war. For two years she was hiding in the barns of good-hearted Russian farmers who were risking their life to save the Jewish girl.

Nowadays Eleonora lives alone in a neat 2-room flat where she knows by heart every centimeter of the walls: she often loses balance and falls down while walking. She prevents hard bumps by leaning onto the walls every time she feels she is about to fall. “I just lean on the wall and then slowly crawl down.”

Eleonora often experienced anti-Semitism in her life. Like her father, she also couldn’t find a job for quite a while. “I knew I was a brilliant economist, and all employers knew that as well. I’d come to a factory, they’d tell me that they will be happy to hire me, I just need to fill out a simple form. The form always had a “nationality” line. The next day the same people would stare away and make up some stupid reason to reject me. This scenario repeated everywhere for two years.” Being a son of a Jewish father and a Russian mother she never felt herself completely belonging to any nationality. “I was an alien for Russians, but there were also Jews who considered me an alien”.

Nowadays despite all the attention from famous strangers, journalists, filmmakers she feels lonely. She has a daughter who lives separately and rarely can help out because she needs to take care of her own family. She has some old friends, mostly coworkers, who are in touch with her, and, very importantly, “Hesed” Jewish charity homecare worker who cares about her on a regular basis.

Eleonora with Sveta, her Hesed curator

She is very grateful for this help but she also feels that she is dependent on the help of others, and this makes her desperate: “It’s extremely hard. All my life I was helping people, and now I’m dependent on everyone.”

Featured on Wonderful Machine

I’m delighted to announce that I’m accepted as a member of Wonderful Machine art production agency.

I’ve heard about the agency and its leader Bill Cramer from various sources including the Business of Photography Podcast, and all the reviews were totally positive, so I decided to send an inquiry. After my website and social media pages were studied by the team I received a message of approval.

The agency helps publishers and companies get connected with the photographers from 44 countries carefully selected for their listing.

Looking forward for wonderful things to start happening!

Here’s the link to my Wonderful Machine profile page.

My work in numbers

I’m taking my time during the current lockdown to reflect on what I’ve accomplished so far in humanitarian photography. One of the most unbiased way to do this is to crunch some numbers. So I went through all the folders with the assignments accomplished for aids organizations, and here’s what came out:

My collaboration with the first humanitarian photography client began in January, 2013. It was JDC and this work changed my whole life.

Since then I’ve been to 43 overseas locations for humanitarian photography assignments.

The geography of the assignments covers 15 countries of the former USSR and the Middle East.

I’ve conducted 626 interviews with the recipients of the humanitarian programs.

Altogether I’ve supplied humanitarian organizations with 18 000 pictures.

This overview, these numbers are mind-blowing to me. The most exciting is the number of people I sat with to conduct an interview. I’ve listened to 626 life stories. More importantly, due to this body of work 626 voices were heard by a community of donors willing to ease the struggles of those and thousands of other people.

I can’t wait for the pandemic to loosen its grip so I could continue doing the humanitarian work.

Photographing an interview

How to conduct challenging interviews while taking pictures? I’m sharing the experience of combining the two roles on humanitarian photography assignments

Lisa Popova. Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. 2019. For JDC

Conducting an interview and taking pictures at the same time may sound overwhelming but this is a usual practice in social documentary photography. After 8 years of talking while shooting, I now feel as if something is missing when I silently click a shutter button or interview someone without a camera in my hands. However, this type of work is full of challenges and pitfalls. Here is how I navigate this territory.

Ice-breaking

Every interview is a journey, a story in its own right. It has a beginning, a climax, and a resolution. Acting in accordance with the arc of this story is key. Things inevitably go wrong when people try to bend the rules by forcing an interviewee headfirst into the depth of traumatic memories, screwing up the emotional peak or cutting short the ending.

Yakov Bronstein. Almaty, Kazakhstan. 2014. For JDC

Even with the best intents in mind, even being wholeheartedly welcomed, I nevertheless break into someone’s private life when I enter a home as an interviewer with a camera. Usually I only have 40-50 minutes for a home visit, and I come in as a total stranger! By the moment an interview starts, we should trust each other, we can’t be strangers anymore.

How to build trust in such a limited time? First off, regardless of introductions provided by anyone who accompanies me, I always introduce myself again. I announce clearly who I am, what I am going to do, with what purpose, and for whom. Often I tell something about myself. Not the whole life story, but some details that will make me relatable, that have some points of intersection with the interviewee. For example, I can point out that I had the same wallpaper pattern in my living room when I was a kid or that my uncle worked in this town years ago.

I try to dive naturally into an interview by blending it with the initial small talk. I start chatting about simple matters like weather or the photographs on the walls, I never announce formally that we’re starting the interview, just the questions and answers get deeper and deeper as the conversation goes.

For a while, I’m not taking any pictures. I let the camera sit on my lap as we talk. Even when I start snapping, in the beginning, it’s only for a person to get used to the awkward sound and look of the camera. While we’re passing the shallow water of the story, there’s nothing to capture there anyway.

Eye contact

Needless to say, eye contact is probably the most important ingredient of a sincere conversation. That’s the main tool for moderating the conversation, as well. Intensive eye contact confirms that whatever is being told is very important for me to hear. If I notice that the story is drifting away, I can easily show it without saying anything, just by moving my eyes away.

However, taking pictures requires breaking this eye contact, often at those very moments when it needs to be the tightest. Every time I bring the camera to my face I feel this inner pushback as if I’m doing something completely wrong.

Here is what’s important to remember in this regard: not every day people get asked about their life experience. In fact, it’s an extremely rare occasion. What usually happens when we are exploring our past? We’re reliving the distant events and disconnect from the current moment.

It’s only the interviewer who should be present in the moment. The interviewee is out there, on their own journey. If I did everything right, by the moment when we get to the peak of the interview, the person just doesn’t notice my camera anymore, it becomes invisible, non-existent. That’s the moment when I turn into a proverbial fly on the wall.

Galina Lev. St. Petersburg, Russia. 2017. For JDC

I always try to start taking pictures only when we’re deep enough into the conversation, and when I see that the gaze has changed, signaling me that the person doesn’t mind being photographed. That’s a gaze of someone who is not posing for a camera, who keeps being herself. If I grip a camera and nothing changes in the posture, intonations and facial expression of the interviewee, then I’m good to start photographing.

What to ask

An interview is always about the answers, not the questions. Of course, I prepare for each interview. I learn as much as I can beforehand about the biography and family situation, about the hardships and challenges. I write down a list of questions but I never pull it out. Arguably more important is how to ask than what to ask. It’s critical to go with the conversation and ask follow-up questions. Once I show that I’m interested in the story, once I’m curious enough about the details, the conversation flows without much effort.

I like to begin with quantitative questions and end with emotional ones. I can ask “how many years do you live in this house?” to put a person at ease, and end up asking “what do you feel when you wake up in this house?”, when I find it appropriate.

Variety of shots

I can’t bring back from a home visit just a couple of similar frames. I’m supposed to get a variety of shots: middle, wide, details. How to get them when I’m only sitting and conducting an interview?

One of the most efficient ways that I’ve discovered is to wrap up the sitting part and ask for a “tour” around the house. Most often people would say - of course, go ahead and take pictures wherever you want. I would reply - please be so kind to be my guide. I want the host in the frame, not the kitchen. I use this “tour” as an excuse to make shots in a variety of lighting situations, with a variety of backgrounds, but I don’t point it out because I don’t want them to think for a second that they are supposed to pose for me.

Luisa Kalenova. Rostov, Russia. 2019. For JDC

Of course, we keep talking during the “tour”, and quite often as we walk we get to some extremely important details of the life story which a person didn’t find appropriate to reveal while sitting.

Another way to get a variety of shots and at the same time to level up the interview is to ask about the most meaningful object or a photograph in the house. That’s what gets people to talk about their collection of cacti or their only photograph of the late dad, or the family library. These precious objects serve as a starting point for the most intimate stories.

Zulun Issakharov with a portrait of his late father. Dushanbe, Tajikistan. 2014.

Ethics

There is a very delicate balance between getting a vivid story filled with emotions and bringing people to a breakdown by asking them about their traumatic past. I never know which question will trigger a breakdown. Nobody can know. If by any chance I get there, that’s a red flag for me. I find it inappropriate to exploit this condition. I stop taking pictures and try to fix the situation. I must put a person at ease in order to continue. At this moment I’m not an interviewer, I’m someone who can listen with compassion and bring comfort. As a famous documentary filmmaker Ken Burns said: “You ought to conduct an interview as if you’re going to bump into them again after the film is out”.

I deal with the memories, and I should be very careful about bringing them to light. Sometimes an interview reminds a therapy session, but I keep in mind that this therapy is unsought. The interview will be over, I’ll go on with my own life, and the person, in many cases absolutely lonely, will stay one on one with the memories.

It’s always a huge honor for me to feel the trust of someone telling painful things about themselves. When at the end of an interview I thank them, I do so in the most sincere way.

Technical aspects

Camera

Photographing an interview puts some constraints on the way a photographer deals with the equipment. I use the first 5 minutes of small talk to make all the camera adjustments. I can afford to preview the pictures on the camera screen only before we get into a serious conversation. Even then, I just check briefly the histogram to make sure it’s not completely off. I have an automatic preview turned off on my camera, so the images don’t pop up on the screen on their own and don’t distract me. I make my eye focus on the composition and my mind on the conversation. I build a picture in my head before grabbing the camera, and only then I quickly snap it. The less time I spend looking through a viewfinder the better for the rhythm and flow of the interview.

Lens

Very often I have to deal with the dark and dull light of Soviet apartments. For these situations I used to carry around two camera bodies with speedy prime lenses: Nikon D750 with 50/1.4 and Nikon D700 with 20/2.8. Nowadays I’m using an amazing Nikkon 24-70/2.8 lens with my D750. It’s bulky but it’s still more convenient than having two bodies hanging on me.

Notes

I don’t rely on my memory to remember all the stories I capture — sometimes I hear a dozen of them in one day. I use my phone to record sound throughout the interview. I don’t use these recordings for anything but writing my notes. I make a quick note after every single visit, on my way to the next one. Usually, I put down just a few keywords which will then remind me what to look for in the recording. I tried all kinds of ways to save these notes, from a paper notebook to Evernote app. Paper notes were hard to use while riding in the car on the bumpy roads. Evernote was a bit too complicated. I ended up using Google Keep for these quick notes.

Backup

Upon getting back to a hotel the first thing I do is make copies of all the files of the day, including the audio files. I copy them to the laptop and to the external hard drive. Additionally, I make Dropbox do its job of uploading all of it to the cloud. Normally I don’t consider myself a backup freak, but things change when I’m on an assignment in the opposite corner of the world.

Ninel Nikolaeva. Almaty, Kazakhstan. For JDC

Clearing mind

Once the files are saved in multiple places, I lay down on the floor and rest for a while in a “dead body pose”. This is a necessary part of my work — a silent meditation that allows me to internalize all the stories I’ve heard and at the same time to separate myself from them. Without this separation a quick burnout is inevitable.

Wow, what a year! My photo take on 2020

Here is a collection of the pictures I’ve taken in 2020. They will remind me of all the ups and downs of that year.

I can’t explain how exactly this happened, but the “stay-at-home” year for me became the most fruitful*, creatively fulfilling, and diverse one, ever. Seems like the global crisis that put our resilience and flexibility to test, forced me to work harder than before, and I was blessed to collaborate with people with a similar mindset.

* With 32.000 frames of stills and roughly 500 hours of video footage.

Choosing the images that would summarize my 2020 wasn’t an easy job. I laughed a lot, I sighed a lot as I was going through the images reliving all the joy and the sadness and the stress of this unusual year.

I’m inviting you to join me on my photographic journey through 2020.

None of this would have happened without incredible artists and organizations that found a way to move forward regardless of the turmoil and provided me with an opportunity to document their projects through photography and videography. Some of the names are:

Thank you, guys. I can’t be grateful enough.

HANIGRARIM: Clowns off the beaten locked down path

From Ramon crater to Galilee heights in Israel, Hanigrarim clowns rock and roll, unlock those locked down, integrate those disintegrated, unite those separated and fix those broken. Unparalleled is the parallax when they are on the move, ungovernable is the roar.

Hanigrarim is a traveling clowns cabaret, an initiative of DAVAI Theatre group who invited the best Israeli clowns and musicians to join the show. The format of the show allows performing even during the lockdown periods.

I'm thrilled to capture the story of the project in its elaboration from the vague idea to the booming success in the streets, fields and squares of the country.

For DAVAI theater-makers it all started in the midst of COVID-fueled uncertainty with buying a trailer that was upgraded to a moving stage. It required a lot of courage to switch gears and invent a whole new show with new participants and no guarantees of any success whatsoever.

The first ads for the show I filmed while it was still under construction but already gained its unique atmosphere and elaborated the characters:

The Birdman (Losha Gavrielov), a clumsy and reckless “ace” that fails a lot but in the end succeeds in taking the whole thing up into the air.

Tesla (Michal Svironi), the ruler of the world and minds, equipped with an external hard-mounted extra brain. She mysteriously can see through people and transmogrify them.

Zak (Fyodor Makarov), this one lacks the brains, as opposed to Tesla. Instead, he’s got an extra set of external muscles that allow him to fold metal rods.

Perla (Limor Eshaek), overwhelms everyone with her crushing love and joy.

Mr. Goldman (Vitaly Azarin), a true mugician (musician+magician), arrived straight from Carnegie Hall with his golden teeth, head, heart and stainless steel saw.

My visual ambitions grew along with the scale of the project itself. Besides the stills, we created a stylish short movie depicting the characters as aliens from another galaxy. Truth is, for those who were lucky enough to have HaNigrarim perform under their windows, the artists definitely were aliens that showed up out of the blue and quickly disappeared in the air.

When you deal with multi-faceted talents such as Hanigrarim performers, creative ideas just outpour. What's even more important and unusual though is that all viable ideas get realized, and very quickly.

HaNigrarim were able to turn the glooming 2020 into booming. They have arrived at December with a tight schedule and had to squeeze up to 13 performances into each weekend.

For the traveling circus, the road is always long and winding in every sense of the word, but the guys just sped through it. After just two months of preparation, dozens of towns and villages welcomed colorful, lovely, unforgettable show that goes way off the beaten path.

Links:

Latest news from DAVAI Group on their FB Page

EVGENIA KIRSHTEIN: Wide-Eyed Art

A rising star of naive art, Evgenia Kirshtein lives in the heart of Jerusalem, in a house constituted of the walls of 4 other houses and a roof. There’s no coincidence in it. Restoration artist by her first profession, currently studying ceramics art at the Bezalel academy, Evgenia is attracted by the idea of rethinking the past.

A few years after moving to Israel from the moist of St. Petersburg, she walks down the chilling winter Prophets street. She's taking a moment to rethink her own past, when she notices an abandoned, wet, unfortunate being left near a dump. That being is a tender and fragile old painting. She can’t pass by the tragedy of oblivion. In the same way as some people rescue homeless kittens, she takes the poor thing home, breathes life into it with her brush and paints, and hangs it on the wall.

Evgenia turns the past inside out. Her works, including those made from scratch, are full of historical references. She can mix ancient Greek pottery concept with her favorite Russian iconography to create a grotesque allegorical depiction of COVID-hit Jerusalem of 2020.

Her sketches of daily life are as naive and straightforward as the reality itself, and the reality doesn’t want to be separated from Evgenia’s sketches.

Even the eternal Jerusalem of stone, so short on colors, suddenly wants to show its essence of a colorful cozy Mediterranean town. Harsh sunlight with deep shadows wants to get transformed into a sentimental playful shine scattered by leaves.

The microcosm of Evgenia’s tiny house with surrounding backyard which is known for its famous inhabitant, Rachel Blewstein, provides endless inspiration. As the sun makes its daily walk across the sky, its light points out various hidden corners of the backyard, revealing to the artist all the well-kept old secrets. This game results in paintings which gradually make the backyard wider and wider known for its new inhabitant and praiser, Evgenia Kirshtein.

DAVAI: A Day in Life of Three Bored Men

As dust settles down after an endless hot summer night in Tel Aviv and merciless sun crawls toward the roofs of the skyscrapers, three middle-aged human beings dressed in drinkers’ rags, wearing rappers’ gold chains and guest-workers’ gold teeth, totter to their usual place. It’s here, in Florentin, between construction sites, graffiti artists’ sheds, one-night stands, one-man bars and one-dancer night clubs, where the 3-men drinking/hangover healing spot is located. Lyosha, Vitalik and Fedya deeply hate intoxicated mornings like this one, but every single weekend the story repeats itself.

None of them ever dare coming empty-handed. Fedya’s dragging a huge black box he just found in the trash, Lyosha decided to treat the friends with a shashlik made of rubber chicken and fish.

Vitalik, the leader of the gang, brings stuff in his luxury roaring motorcycle: a bottle of pink drinking petrol to treat the hangover, a golden toilet bowl for the most pleasant throw-up experience in the world. He would also bring a washing machine, but Fedya and Lyosha didn’t want the boss to get tired, so they carried this important piece of picnic equip themselves.

Finally, everything’s ready to celebrate the dull morning. Vitalik sips some petrol. When he recthes, somehow a fire bursts from his mouth. That’s a fire of anger and disappointment mixed with yesterday’s fake Absolut vodka. Lyosha sets Vitalik’s motorcycle on fire to cook the rubber BBQ. He knows the best recipe and it’s better to stay away from the chef as he cooks. Fedya jumps atop washing machine and starts singing a rap song. Everyone hates the song but can’t resist taking over the tune which goes like this: “Mama-mama maya! Mama-mama tvaya!”.

Middle-aged bored rappers are singing about their difficult but rewarding life at DAVAI - a huge construction company they own, which is busy building highly over-priced real estate all over Northern, Western and Eastern Tel Aviv, including its upper lands and lower lands. Famous DAVAI Tower located in the heart of Florentin district hosts the headquarters of the company, and most of the time the three men spend their working days there, thinking over investment plans, making important strategical decisions.

As the song progresses, it becomes clear that life at DAVAI is flourishing. Twelve new floors are being built every week, millions of dollars get buried in the ground, about a dozen of weaker competitors get thrown out of business every month (and buried in the ground). The guys work hard. They deserve a truly good rest.

Money is not an issue for the gentlemen. They can afford inviting best and most expensive photographer, videographer, dronographer, chronographer and choreographer to cover the day in their life. It’s really important to have a good photographer on occasions like this. A distorted visual image created by a less experienced photographer could ruin their shiny-white reputation, the business men know it well.

After healing the hangover the friends get a bit elevated. They head to the nearest graffiti-covered wall to pose for the photographer (me) pretending that they are dancers. Artur, a fashionable TLV choreographer, shows up. He only moves a finger slightly to point out some minor hiccups in otherwise perfect dance routine. Vitalik dances like crazy, hitting the walls with his chest. Lyosha dances like crazy, hitting the floor with his butt. Fedya dances like crazy, hitting the air with his hair. Everyone dances like crazy. Next to a nearby dump, a rat and a chasing her cat both freeze in the jump, shocked by the unforgettable performance.

Tired of dancing and of their own hot pulsing energy, the men walk to the DAVAI Tower. Vitalik rides his luxury three-wheeler, he hates being seen walking like a poorman.

A brand new idea comes to their minds as perfectly conditioned air of the crystal-clean office touches their faces.

They want to break the rules today. They want to turn - just for one day! - their dull money-making factory they’re accustomed to, into a real muddy mess. They want to free themselves from the formalities of the business life. They decide to invite to their office a real Swedish death metal band! They call their Stockholm partner from GRUNDTAL/NORVIKKEN group, which in turn immediately gets in touch with the band’s senior producer, and half an hour later a private GRUNDTAL/NORVIKKEN jet with the dirty death metal musicians onboard is dissecting a freezing Scandinavian air.

[The band didn’t want their name published for understandable reasons.]

Waiting for the miracle to come

While waiting for the musicians, Lyosha, Vitalik and Fedya cook themselves some delicious hummus-filled pita sandwiches, something only affordable for TLV VIPs these days.

The loud, crashing, detonating fun is all they are looking for, and the Swedes don’t disappoint. At the peak of the performance two of the musicians even gouge their eyes right in front of the DAVAI leaders! They get paid enormous money, so they don’t care about losing their eyes. They want to please by shocking, they want to indulge by screaming and growling. Dust and smoke, extraordinary decorations and real demolition of the office walls make Lyosha, Vitalik and Fedya chuckle in total satisfaction.

Time passes, another night is approaching, and DAVAI top managers want to make it even more unforgettable than the morning and afternoon. What could possibly wish someone who obtains everything in the world by a simple snap of two fingers? Of course, love! Pure, sincere, overwhelming, the type of love a human can get only as a child. So they go for it. They order an exclusive entertainment - a time machine which turns them into cute little toddlers who own a tit of gigantic size. Tit jumping is something Vitaly, Lyosha and Fedya would love to practice more often, but the price is so astronomically high, that even these multi-billionaires can only afford it once a year. The three get a special entrance permit to a closed-off secret area where they get what they want. Pink Tel Aviv sunset serves a perfect backdrop. Pink ridiculously large tit makes the men totally happy. Oh yes, it made sense to work that hard all year long to get this golden hour of tit jumping. It paid off, no doubt.

Blessed and exhausted, Vitalik, Fedya and Lyosha jump off the tit and jump into Fedya’s cabrio. They speed back to DAVAI tower to wrap up the day. Unfortunate, poor, somewhat happy, drunk, wasted, amorous, angry, tired, energetic, abused, scared, melancholic, doomed - all kinds of Tel Aviv humans they pass as they rush through the night streets, but they meet no one nearly as accomplished as they are!

The day ends in the office. By this hour it’s already renovated and shiny clean again. Vitalik pulls out a crispy bottle of Absolut vodka from the fridge. He swears that it’s not fake this time. How he knows? Because he paid a big buck, 80 NIS for the litre. Lyosha drags out pickles from his bag. Fedya tries to find something to put on the table, too, but fails: a half of pita bread which he hides in the plastic bag will serve him a late night dinner and maybe a breakfast, too.

At midnight, sharp, Vitalik, Lyosha and Fedya will go to the TLV waste lands to dig out a few millions from the ground to survive through the next week.

“My name is Matvey-and-Ignat”

A moment in the life of a large family from Yekaterinburg, Russia.

Russia, Yekaterinburg. A regular winter day’s night.

Matvey and Ignat are busy doing homework. They are twins. When I ask one of them what is his name, he replies: "Matvey and Ignat".

Eva hugs Daniel, her beloved older brother.

Daniel is "busy doing nothing", as he defines it himself. He survived a suicide attempt and is recovering with help of his large family.

7 family members (or 8 including a huge dog) share a standard Soviet-era 3 room flat. Family gatherings around the table are impossible due to the kitchen size - over 3 persons just don’t fit in it.

The last bus

Pinega region of Northern Russia is a place where anything has the potential to become “the last” in retrospect. Here’s a bus that suffered this fate.

Pinega region of Northern Russia is a place where anything has the potential to become “the last” in retrospect. Here’s a bus that suffered this fate.

A simple and bleak offspring of Pavlovo bus factory (PAZ), for decades it served as a key player in the fragile eco-system of villages, giving the people a semblance of freedom of movement. It operated several days a week and connected the district center with a dozen of villages located down the river. It allowed people to travel for such essential necessities as visiting a doctor, buying houseware and clothing, seeing a bank clerk or a lawyer, coming for a summer festival.

Not always the bus was able to reach the village itself. On this picture the passengers get off and walk over 2 km across the river and then up the hill to get home.

March 2009. Pirinem, 41 km from the district center Karpogory

A large timber enterprise was built in the area a few years ago. Instead of bringing improvement to the region, it only sucked out the last resources. The bus company that was in charge of public transportation, began providing services for the enterprise. Obviously, the timber magnate pays better than a bunch of starving seniors from the villages.

There is no bus for the villagers anymore. The public transportation is halted altogether. The majority of those who live in the villages don’t own a car, and their last resort when they need to go see a doctor is booking a taxi, but the prices are outrageous. For most people it takes 2-3 round trips to the district center to run out of monthly pension which is their only source of income.

Warming up after a chilling night

December, 2010. Kusogora, the final stop of the bus, 52 km away from the district center Karpogory

In my first several trips to Pinega I traveled by this bus a lot. Nikolay, the driver, recognized me a year after my previous trip and remembered where I need to get off. People often asked Nikolay to deliver something. On this picture he’s delivering from the district center a spare part for someone whose car broke down. Charging money for this service was out of question for Nikolay, of course. Nikolay was everyone’s friend.

March, 2009. Shotogorka, 33 km away from the district center Karpogory

December, 2010. Kusogora village, the final stop of the bus, 52 km away from the district center Karpogory

October, 2011. Near Shasta village, 45 km away from the district center Karpogory

March, 2009. Pirinem, 41 km away from the district center Karpogory

October, 2011. Near Shasta village, 45 km away from the district center Karpogory

October, 2011. Cheshegora village, 38 km away from the district center Karpogory

Nursed and being nursed

Among all the amazing people who get help from the JDC in the former Soviet Union there is an extraordinary category: nurses. They spent their lives helping others and then found themselves in need of nursing.

Among all the amazing people who get help from the JDC in the former Soviet Union there is an extraordinary category: nurses. They spent their lives helping others and then found themselves in need of nursing.

When I was a kid, I was under the impression that all healthcare workers are protected from any diseases by virtue of their miraculous profession. Later I realized that they are as vulnerable as anyone else. The ongoing COVID crisis showed that they are way more vulnerable, risking their lives on the front lines of their peaceful job.

I want to share with you several stories of the nurses that are currently under the JDC’s protection. These stories simply must be told to honor the heroes.

Sonya

Kazakhstan, Almaty

On this picture from 2014 Sonya is 90 years old

“I experienced famine before the war, including Ukrainian Holodomor in 1930s, then the starvation of war, then famine again. During the war I was working as a diesel generator technician. I was the only woman there, but I could gear the generator although it required a lot of physical power. I was constantly hungry and weak. One day when I already felt like I gonna die of hunger, one woman who barely knew me, shared with me her potato. Just a half potato, but who knows, maybe it saved my life!

After the war I began working as a nurse. I had about ten addresses to visit all over the district each morning. When I saw a patient that beyond a medical procedure needed lighting a fire in a stove or bringing a bucket of water from a well, I didn’t think twice and always helped.”

Up to now Sonya, as well as many others from her generation, has special relations with food. She tries to eat as little as possible, always saving something for the future and for the others. “Bring me just a cup of boiling water, please” she asks a helper during the lunch at the JDC charity canteen.

Sonya lives alone in a tiny and shabby private house. She needs help all the time now. “Without a homecare worker, I’d already be dead”, she says. Even essential tasks such as opening a tin-can turn into a challenge for her.

Sonya has just one daughter who is also JDC client with a whole bunch of health issues. Sonya would love to have more kids but due to her husband’s injury they couldn’t have more children. “I didn’t leave my spouse although I was dreaming all the time about having more children. I don’t betray my friends.”

This resonates with a global idea behind JDC organization: not leaving friends behind.

Katya

Ukraine, Odessa

Katya with her husband and daughter in 2016

One freezing night in December 2013 a kitchen in Katya’s tiny old flat caught fire. Her husband woke up to the heavy smell of smoke. He rushed into the kitchen and tried to extinguish the fire but failed. He managed to get his family out of the house, but got severe burns which took months to treat.

The morning came. Katya’s flat was destroyed, her family couldn’t live there anymore, her husband was in the hospital. Everything suddenly fell apart. What Katya did in this situation? She just headed to work! She is a nurse at a hospital, people were waiting for her there and she had to be there for them.

Katya didn’t tell her colleagues about the disaster. It was only after they noticed the smell of smoke coming from her that she told about the fire in her house. The hospital where she was working offered a shelter for Katya and her family, and they lived there for weeks.

Katya’s burnt out kitchen. Yes, this is a kitchen, there’s no mistake. This 6 sq.m. unit had kitchen, bathroom and toilet squeezed into it.

Tatiana

Moldova, Chisinau

On this picture from 2016 Tatiana is 98 years old

It takes a while for Tatiana to notice me shouting her name from her backyard: she barely hears. It takes quite a while for her to get to the front door: she can barely walk. It takes a few more minutes to figure out how to light up her completely dark house: Tatiana is blind and never switches the lights on.

Her tiny private house is now her only friend, her only reminder of difficult but happy young years. She built it herself with her late husband. They put money aside for years to finish the house, but all they could afford were the cheapest materials, and now the house is falling apart. The floors are full of huge cracks, the roof leaks.

Tatiana is someone who dedicated herself to saving lives. She took part in two wars – with Finland in 1939 and World War II. She was a nurse who dragged under the fire countless wounded soldiers from the battlefields. After the war she was working as a nurse at a hospital, and kept saving lives until her retirement. All she got from the country for her heroic efforts and hard work is a pension of 66 USD a month. Without JDC financial support and home care she wouldn’t be able to survive.

Perel

Ukraine, Zhitomir

On this picture from 2016 Perel is 86 years old

Everyone knows Perel in her town of Zhitomir: all her life she was working as a delivery nurse and these hands helped bringing thousands of people into this world.

This didn’t stop her anti-Semitic neighbors from cutting the old lonely lady off water communications. One day Perel found herself without running water and even toilet. This was a result of a renovation of the neighbors’ part of the house.

For Perel the absence of immediate access to water is not only humiliating, it’s a disaster: as a hereditary medical worker she’s used to keep everything perfectly clean. Now even visiting a toilet turns into a nightmare: she has to use another neighbor’s restroom, every time asking permission to enter. She has to go to the JDC office to take a shower.

Ironically, in exactly same part of the house where Perel lives, used to live famous Jewish poet Khaim Byalik in his childhood. His memorial plaque had to be taken off the building’s wall and put for storage in the local Jewish museum out of fears of anti-Semitic vandalism coming from Perel’s neighbors.

The lifeline for her is home care service that she gets from JDC. Perel has a great, dedicated homecare worker who readily helps with everything. Most importantly, this woman every single day brings her water in buckets. "The nearest stand-pipe is some 300-400 meters away" tells homecare worker, “Usually I go there 5-10 times a day: Perel needs water to wash herself at least a little bit, to cook, to clean the floor, to make some laundry. I'm lucky if the nearest stand-pipe is functioning but often it’s broken, and then I have to go to the next one which is a kilometre away."

The only source of water is the bucket filled for Perel by a homecare worker.

As Perel tells about her life, she often gets back to the topic of JDC: this organization is now nursing her just the way she used to nurse her patients, providing support, confidence and loving care.

"It begins with a security guard who opens the front door of the office. He is so nice! I remember, I’d been sick for a while. After I recovered and came over to JDC, this young man asked me if I were feeling better! Turned out, he was aware of my illness! Now you understand the degree of attention we receive there? It's big deal! When I come there, I feel that I'm welcomed. I'm very sensitive to such matters. JDC is my real second home, and very cozy one."

Mother’s Day picture

Masha with her mother.

Masha is 16 on this photo. Severe cerebral palsy made all her body twisted. She weighs 20 kg (44 lbs), all her organs are underdeveloped. She will never be able to say "thank you" to her mother Anna for all her love and selfless care.

I took this picture on this day 4 years ago in Kyiv, Ukraine

Soviet era home

Decades passed after the Soviet empire collapsed, but thousands of households are still keeping furniture, decor and houseware purchased in 1960s-1980s. Apartments turned into museums of Soviet lifestyle mainly because their owners simply couldn’t afford any renovations or upgrades.

In my photo expeditions to the former Soviet Union almost every day I have these déjà vu moments when in someone’s apartment I run into the same chandelier as in my childhood room, the same wallpaper as in my granny’s living room, wall clock like in my friend’s house. Soviet regime was famous for its total standardization of everything.

Decades passed after the empire collapsed, but thousands of households are still keeping furniture, decor and household items purchased in 1960s-1980s. Apartments turned into museums of Soviet lifestyle mainly because their owners simply couldn’t afford any renovations or upgrades.

The pictures below are taken in 2010s all across the former USSR. Under the photographs you’ll find short explanations.

Russia, Rostov. 2019

New Year toys. New Year (“Novy god”) up to now remains the most widely celebrated festival of the year. The attributes of the celebration remain unchanged throughout generations: decorated new year tree, Grandfather Frost (“Ded Moroz”) and his granddaughter Snow Maiden (“Snegurochka”). A set of New Year toys was kept in every household. The same set could serve a family for several generations.

Cut-glass bowls. Typically, these grand vases were presented as gifts to the employees of state enterprises to mark various life events or accomplishments.. It wasn’t common to buy such things.

Ukraine, Odessa. 2016

Wired-radio outlet. A radio hanging on the wall used to be the main source of news in Soviet times. There were two basic types of such outlets, one allowed to switch between 3 pre-programmed stations and the other one would only allow listening to one wired radio transmission. The radio on this picture is connected directly to a special radio wall plug and can receive only one station’s wire-transmitted signal.

Wall decor. Wallpaper was a standard way of decorating interior walls, not only in urban areas but in rural private houses as well. The family residing in this room lives way beyond the poverty edge. They couldn’t afford a wallpaper, but having a wall just covered with paint was so uncommon that the residents tried to draw an imitated wallpaper pattern.

Moldova, Balti. 2017

Geyser. Gas water heaters were widely used in the houses without central water heating and with central gas supply. To heat water we used to insert a match into a handmade wooden extension stick, light it up and push it deep into the small black hole where it would ignite a large burner. Theoretically the geysers had their own ignition systems but they never worked.

Moldova, Chisinau. 2018

Periscope, steering wheel. Stealing stuff from work was a commonplace in Soviet Union. Households were decorated with unusual boodle in the same way as hunters show off their kill. The resident of this room used to work at a military enterprise.

Massager. A massager with wooden wheels was extremely popular in 1980s. It had handles on its ends, and we’d pull it from side to side to massage a back.

Page-a-day calendar. Another item that every family had was a tear-off calendar. There was some variety of them, listing different kinds of information for gardeners, kids, women, hunters etc. A day in a Soviet family would begin with tearing off yesterday’s page and studying its back which could contain an “on this day” information or a poem, a picture or a piece of household advise.

Brown and black St. George’s ribbon. The ribbon’s history goes back to 1730s when its colors officially became the colors of Russian Empire. In 20th century the ribbon became one of the symbols of WWII in Soviet Union, and in 21st century it’s going through a revival. It became a symbol of Russian victory and glory and a way to show support to Russian government.

Russia, Saint Petersburg. 2018

Shared kitchen in a communal flat. It’s hard to believe but “kommunalka” dwellings didn’t extinct yet. In St. Petersburg right now 245 thousand families share 76 thousand flats (approx. 3 families per flat). In kommunalka every family normally has a separate room and common space which includes corridor, bathroom and kitchen.

In a kitchen every household aims to have a separate cooking table with own set of cookware and a separate stove or at least a part of a stove. Sometimes the residents have to take turns in cooking due to the lack of space or stoves. Usually each family uses its room for eating, so there are no dinner tables in the kitchens.

Ukraine, Nikolaev. 2016

Shared bathroom in a dormitory. If you are thinking that there is no worse place to live in exUSSR than famous "kommunalka” (a shared flat), you are wrong. “Obschaga” (a dormitory) is much, much worse. A typical kommunalka would host 2-5 families whereas in a dormitory one has to share living space with 10-20 other people or families. Kommunalka in a city like St. Petersburg could even have some remnants of luxury life such as a high ceiling or a fireplace, because historically a shared apartment could actually all belong to one rich family.

Dormitories were normally built for workers of huge state enterprises and they are ugly by design. After USSR collapsed and the enterprises fell apart, the dormitories turned into dwellings for the poor. In the lack of proper maintenance they are degrading and become unsuitable for life, but those who have no other choice keep living in these creepy buildings.